Zork I: The Great Underground Empire

In the beginning, there was Adventure, released in 1975 by a computer scientist and amateur spelunker named Will Crowther, written in the FORTRAN language. I don’t know which is more adventurous—caving or using FORTRAN—but at the time, that’s what was available and little else. Exploring caves certainly offered several advantages, including knowing how to skillfully write a text adventure set in an intricate labyrinth of underground tunnels.

This stone labyrinth had some similarities to the Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, which Crowther had actually explored.

The definitive version of the game that made history was the one modified by a certain Don Woods, a student at Stanford University. A lover of Tolkien’s work, he added fantasy elements, effectively creating the first fantasy RPG in video game history, of which Rogue from 1980 would be the true precursor.

But the apotheosis of text adventures would come in 1979 with the completion of Zork and the founding of Infocom. A first version of the game had already been released in 1977 for the PDP-10 mainframe, laying the foundations for what was to become a milestone for text adventures and video games in general.

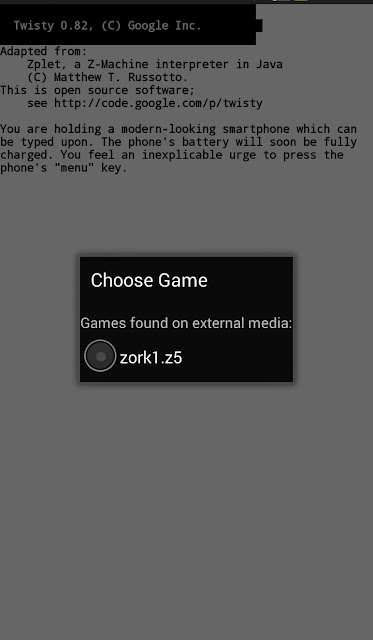

Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling—four big nerds from MIT—created a special programming language called ZIL (Zork Implementation Language or Zork Interactive Language). It was executed by the virtual machine Z-machine, greatly facilitating porting between different platforms. It was sufficient to convert only the virtual machine into the target native language, and the game was ready. Thanks to this method, today we have applications like Twisty for Android, written by those fun-loving folks at Google Inc., and Frotz for iOS, which are nothing more than the dear Infocom Z-machine implemented on modern platforms and capable of running all text adventures written in the Infocom Z-Machine format (files with the ‘z5’ extension).

Replaying Zork on a cell phone or tablet has its charm and is certainly a portable game of an intellectual level a tad higher than certain junk played by casual gamers on buses or in any waiting room.

But let’s get back to our Zork, which was born as a single adventure but quickly transformed into a trilogy because the platforms that that were to host the game—the first 8-bit home computers—did not have enough memory to contain it all. So it was divided into three parts. Despite the narrative continuity of the trilogy, each part was given a certain independence so you could play any of them and still understand what’s going on. In this article, we will deal with the first part, the debut of our hero and his entry into the great Underground Empire of Zork.

An interesting anecdote is that the definitive version of the game was supposed to be called Dungeon, and that Zork was actually the nickname given at MIT to unfinished software. But when it was time to change the name, ‘Zork’ had such a hold that they decided to keep it.

Explaining what a text adventure is seems superfluous, but suffice it to say that in a world where video game graphics have reached levels of realism never seen before, it’s still possible to play and have fun with a video game that, like a book, describes in literal form the player’s state and environment and accepts commands in written form from the player.

In this, Zork was a true champion, as it had a highly evolved parser for the commands typed by the player and was able to understand even complex phrases like “hit the troll with bloody axe.”

As for the graphics, to paraphrase a beautiful phrase by Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory, Zork ran on the most powerful graphics engine in the world: imagination!

But let’s try to introduce newcomers to this wonderful virtual environment that is the underground world of Z in Zork, trying to do so in spoiler-free mode.

In the year 948 GUE according to the Zork calendar, our nameless adventurer begins his story in a clearing in front of a large white house, which will reveal a passage to what will turn out to be a vast Underground Empire inhabited by monsters from the fantasy genre such as trolls, cyclopes, and others of Zorkian creation like the terrifying Grue, who will reduce you to pulp as soon as you remain in the dark in the labyrinthine caves when any source of light, such as torches or other devices, ceases to function.

The game’s parser works wonderfully, and you can command your adventurer to move anywhere, interact in various ways with the game world, examine anything, pick up objects, manage them in an inventory tucked into backpacks and other containers you can carry with you (within limits), or store them in chests you leave on the ground, use magic, perform even complex magical rituals, and much more.

A plethora of actions to make even the graphic adventures and the most recent games envious.

You’ll have life points to manage, losing which will result in death, and a score reflecting your progress.

The score increases as you explore and find all twenty treasures hidden in the underground labyrinth that, in addition to narrow tunnels, will present you with complex environments like monumental rooms, dams, rivers and waterfalls, and entire landscapes.

The Infocom Z-Machine processes files with the ‘z5’ extension… and there are a myriad of text adventures online, old classics and new ones created by passionate amateur users.

Everything is managed in narrative mode, and even the battles, once your move is registered, are accompanied by sometimes complex descriptions of events, followed by waiting for new input from you.

A negative note can be made regarding the sometimes excessive difficulty of the puzzles to solve, some of which have very complex logic and are hard to grasp by those who didn’t design the puzzle themselves.

Don’t feel excessively stupid if you have to resort to a game solution: the game is indeed very difficult to complete without hints.

Personally, I am convinced that text adventures are among the adult pastimes par excellence, thanks to their similarity with reading a book, the narrative complexity they often possess, and the wit of the puzzles to solve. But unfortunately, the deep general ignorance in this area makes them certainly less accessible than a Sudoku, a crossword puzzle, or reading a novel.

The Verdict:

Zork was the origin of several things including fantasy RPGs on computers, the first true text adventure, and the birth of an epic that, after the original trilogy, continued with numerous video games until 1997.

It’s a piece of video game history of paramount importance, and if you love video games, you cannot miss it.

Pros:

- The narration of a text adventure is often superior to the average video games we’re we’re used to, and Zork is no exception.

- The complexity of the puzzles and the actions executable through written commands is still unmatched by any other modern video game.

- “Hit! Troll! With! Axe! HIT! TROLL! WITH! AXE!”

Cons:

- Excuse me?! Could I have some graphics, please! What’s that? The graphics are all gone? Ah well… I’ll make do without…

- The puzzles are sometimes devilishly difficult.

- The absence of a learning curve: the text parser may take some getting used to, especially for players new to text adventures.

| Score | Rating |

|---|---|

| Commodore 64 Game | 96% |

Comments

Post a Comment